To help our disabled clients as much as we can in our sessions, we can ask them questions about how they would like the session structured, like we do with all clients. Its not singling them out, but it is giving them an opportunity to discuss their needs and how we can best work together, since they are the expert on their own disability. As mentioned in the paper, asking “How do you learn best?” is very similar to asking how they would like to proceed in the session. We could even right-out ask how they best learn, but that might not always fit the context of the session as well, and may make them feel more singled-out in their disability. Being patient and checking in with them if they seem hesitant or confused on if they understand a concept would help, as well, although these are also practices put into place with other students already. If they are willing to bring up their disability, it’s great to know where they are coming from so we can get a better picture on how to help them, but otherwise just meeting them where they are in their writing and helping them where we can, is something we do with all students, and is essential for those with disabilities.

JR 26

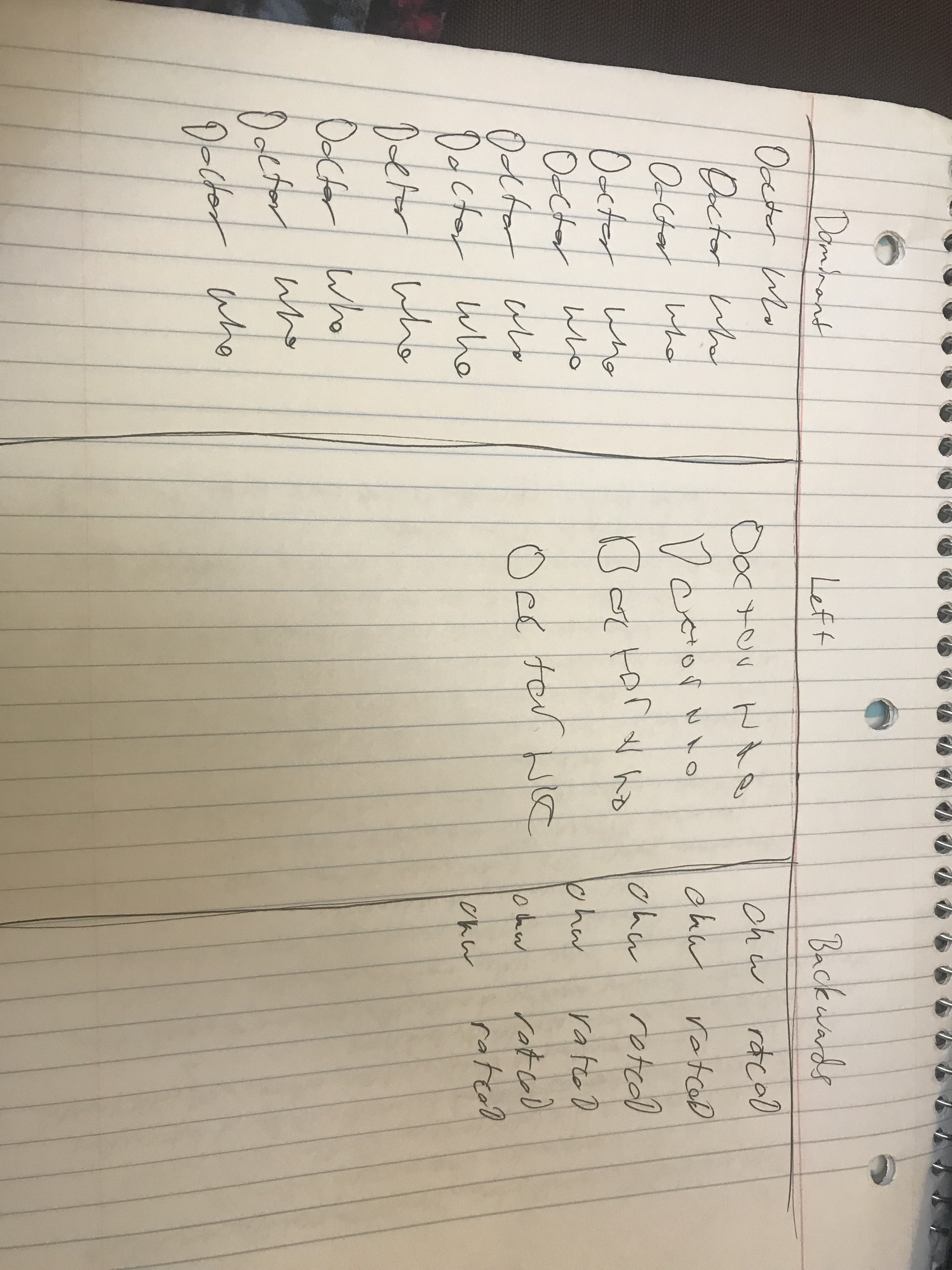

This activity was pretty difficult, especially since even my normal handwriting is hard to read for some, but I wanted to go as fast as I could, while still keeping it somewhat legible. The left-handed was the most difficult by far, as my hand just couldn’t move in the way I wanted it to, which was frustrating. The backwards started out difficult, with a lot of thought put in, but then got better as I got used to it, and I was able to copy the ones I had written above.

I believe both physical and learning disabilities could be equally challenging to students, depending on the severity. Physical disabilities can make it difficult to learn, because they can’t do it in the same way as every other student. The left-handed activity probably represented this, since our non-dominant hand can’t move the way we want it to, which significantly slows down the ability to write. Learning disabilities can also be significantly impairing, and it depends on the severity and the amount of intervention they’ve had access to over the years, but it can be just as severe an impediment as physical. Writing backwards took much more thought than writing with my dominant hand, or even my left hand, and then I came to rely on copying my own work to help speed up. If I had had to write a different word each time, it wouldn’t have turned out so well, and probably would’ve been harder to do than writing left-handed.

JR 25

The Dangerous Method, in which the writer free writes until a strong idea is found, is something I use often in my creative writing process. Whenever stuck, whether in a scene, or in the entire novel structure in general, I will write out my thoughts until I have a moment of clarity, although sometimes it takes longer than others. I’ve never applied this to scholarly writing, as it feels too loose to associate it, but it is a possibility if the prompt is vague, or leaves wiggle-room. Loop-Writing is very interesting, almost a more structured version of the Dangerous Method. I have not done this before, but I could see how it could apply better for brainstorming scholarly papers. I have used a loose version of some of the question-asking strategies mentioned in the Invention Strategies before with students, but have never tried it in my own writing.

The Dangerous Method is most likely the one I would recommend, because I am more familiar with it, but more for argumentative or open-ended essays. A topic where the opinion is the main focus of the essay, and the student does not know what they think, or which lens to use. However, some of the invention strategies would be really useful, as well. Exploring a topic through questions was my favorite one included in this section, as it creates a natural tutor/writer give and take: the tutor asks questions surrounding the topic and directions, and the writer generates their own ideas to answer them. This is similar to things I’ve already done with student writers, but to focus it even more to questions on concepts, propositions, and what the writer wants the audience to take away from the paper, will definitely help them generate a strong foundation for their paper.

JR 24

Getting started on an essay is really dependent on the directions and framework that the professor has given. Sometimes they directly tell you what they want with topics to choose from, which makes it very easy to pick a topic and get started on an outline. If it’s more open-ended, I typically pull ideas from the content we are writing on (movie, book, research) to generate ideas for my thesis. Sometimes I know what I want to write about in general, but I don’t know the specifics, so I do my research and outline the body paragraphs of my paper, then tailor my thesis to fit the subtopics I chose. When outlining, I will pull directly from articles/papers/books the evidence/information that I want to include to organize my body paragraph topics. I reword these when writing my paper, but it’s just easier to access when it’s already in my outline and I don’t have to look up each source again to find each bit of information. My commentary, unless really unique, essential, or something I’m worried I’ll forget, gets left out of my outline and instead comes out when writing.

My brainstorming strategies have become more sloppy, but also more efficient, since high school. I used to create outlines with mostly my own ideas, not with the evidence from texts. Now I do it the other way around, which helps me a lot, since I already know my own ideas, and they organize themselves around the content I choose. If it’s more of a creative process, however, my brainstorming process has been the same since about seventh grade: free write about my writing until something significant appears. Before that, I would just dive right into writing, the ideas barfing themselves out while I create the first draft.

The only brainstorming sessions I’ve done have been with long-answer quizzes, where the answer is straight-forward. Since we didn’t create an outline, I just asked questions and gave general suggestions for answers, which helped them get their own ideas for the answer. This is very different from what I do as a writer, however, it is a different situation than a normal essay.

JR 23

Understanding Writing Assignments: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/688/01/

Effective Outlines: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/544/01/

Chicago Style: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/717/01/

Writing a Book Review: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/704/01/

Thesis Writing Tips: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/545/01/

Essay Writing: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/685/01/

Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for Exploratory Papers: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/728/01/

Writing in Psychology: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/670/01/

Descriptive Essays: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/685/03/

Personal Statements: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/642/01/

Resumes: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/564/01/

Subject-Specific Writing Resources: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/section/4/

JR 22

What are typical reading problems experienced by writers?

Some readers have trouble with basic understanding, but most struggle with being able to do more than summarize the material, such as analyzing, understanding author’s purpose, or being able to refute the author.

How do we assess problems and establish priorities?

Ask the student questions about their reading strategies and how much they actually understood, and ask if you have the time to address these if there are problems in their reading comprehension.

How do we improve basic comprehension and interpretive abilities?

By asking reconstructive questions to help them understand the reading and substantiate their claims; interpretive questions to have readers get to the importance of their reading, why an author would be writing on the topic, and if the author has credentials to write this; and applicative questions to apply a lens to their reading, and relate it to their own life experiences.

What do we achieve by asking questions about vocabulary?

We help improve the student’s understanding of a passage by looking up or explaining words that didn’t make sense to them before, helping them to get a clearer picture of the text and what they should write.

How does reading the assignment help?

It helps us focus our questions for the student, to know which questions to ask, and to ask questions about the assignment and/or the reading.

How do we improve concentration?

Asking questions about when the reader reads, when they lose concentration, and what they think about when they lose concentration, can help us get to why the student isn’t focusing. We then can offer solutions, such as not reading in one long chunk and take breaks, or read in a less distracting environment.

What is activating the reader?

By skimming chapters and headings, a reader can get a better big picture of what they’re about to read, so they can apply specifics to the main idea of the chapter, and turn headings into questions to be answered.

How does note taking improve comprehension?

It helps readers put the reading into their own words, enforcing understanding, and makes the reader review the main ideas of what they just read, enforcing retention.

What are typical problems of writing about reading and solutions to those problems?

Attribution failures, when students don’t assign credit to ideas or quotes, is common. By asking a student where an idea came from, and seeing if they paraphrased or quoted, will help the student see their issue.

How do we handle overquoting?

Ask writers to rephrase their quotes to paraphrasing.

What is quoting and reconstructing without comment?

When a student uses a quote, but then doesn’t talk about its importance to the whole of the paper, or relate back to an idea being discussed. We can ask them questions about the quote, asking why it’s important, or what the connection is.

How do we avoid framing quotations repetitiously and awkwardly?

We can brainstorm with students on different ways of introducing quotes with different words, or rewording the sentence that the quote is in.

This chapter talked about struggles students commonly have in reading, and when reading to write. We, as tutors, can help students become better writers by giving them strategies to become better readers. One strategy is to take notes, as shown above, helping with understanding and retention. Analyzing a text can be difficult for some students, when unsure of vocabulary in the directions or passage, so looking up words should be encouraged. By asking reconstructive, interpretive, and applicative questions, we can help the student comprehend, understand the greater context, and use it effectively in papers. Asking questions to guide the student to their own realization helps them to learn what they did wrong, and have the answer in themselves to be able to fix it next time. This also happens through giving students strong reading techniques, as mentioned above.

JR 21

My very first session was with a student from a 300-level CS class, a topic I know very little about. However, I did not tell him this, because it didn’t seem important to me in helping him overall with writing. I did ask him questions occasionally to make sure what he was writing was, indeed, answering the prompts correctly, so that was probably an indicator. My lack of familiarity probably empowered the student because it made it so we were working together on the paper, and we were both learning from each other. It put the student in a kind of seat of authority on the topic, and helps them see me as an equal, not an authority. The help I gave the writer was helping him follow the directions for how much of each section the professor wanted, and a lot of MLA formatting help. I have worked with the student again, and will in the future, and so far I wouldn’t do anything differently. He is getting better at following the assignment directions and formatting every time I meet with him.

JR 20

Guarding the Tower: In which the teachers acts as a protector of academia from those who are don’t fit in the learning community. This creates a toxic divide between teacher and student, making the student feel down about their writing, and the teacher feel hopeless about teaching.

Converting the Natives: The teacher accepts teaching some troubled students, but views it as filling up a void with knowledge. However, the teacher doesn’t consider the student’s perspective when writing and learning.

Sounding the Depths: The instructor observes himself as a writer and teacher, and his students as writers with unique challenges. The teacher introduces generalities to help cover as much information potholes as he can.

Diving In: The teacher must accept his students as a part of the teaching/learning process, he must try to understand them to get to both their difficulties and talents. Teachers must design their teaching not for the general student, but for each individual, and must accept the challenge of teaching them.

As tutors, we are using our time with the student to teach them, and in a way become teachers. I’m not sure anyone had the view of Guarding the Tower when going in to tutor, but this could maybe relate to the feeling of being overwhelmed when presented with a paper that is riddled with errors. We avoid this stage, however, by pointing out what the student did well within the paper, making sure the student is aware of their strengths. Converting the Natives could have been us, the interns, when we first started; that we were throwing out information to the student writer, trying to pack them full of as much information before they left the session. Our readings about meeting the student where they are, not where we think they should be, helped us get out of this, although many times I still am struggling to not speed through and try and hit on every single thing I saw. Sounding the Depths is us as we read through the students’ papers, especially if we have return clients. We get a sense for where the student is at, and what their challenges are. We point out the specific errors, and then provide them with a general rule to cover it. Diving In is when we collaborate with the student to get them to where they want to be, such as asking what they want to focus on. When we identify their strengths in the paper, and the areas they need to work on. Seeing the student as an individual and getting to know them can also help us, as tutors, work with them on an assignment.

JR 19

The best teacher I’ve ever had, probably the best one in existence, is Drew Moneke from West Salem High School. On the very first day I had him for APUSH, he gave what he calls his “Demigod Speech” (referencing how Benjamin Franklin referred to the men at the Constitutional Convention as “demigods”). He made us all stand up on our chairs, international flags and European art hanging over our heads, and told us how impressed he was by us for just taking the risk of this class, in the most empowering and touching way. He had us all floored, and right then and there, he became everyone in the room’s favorite teacher. Everyone who had the other APUSH teacher thought their teacher was best, until they had Moneke the following year for AP Euro. Every single person conceded that he was the best, even without being given the demigod speech. He always challenged us to do our best in the most positive way. I didn’t like history before APUSH, but before that class was over, I was already voluntarily signing myself up for an extra year of history with him–best decision ever. AP Euro was the best class I’ve ever taken. We had philosophical discussions, a French Revolution simulation, and a full-out European Salon where we dressed as an Enlightenment figure for the day, and came together to have discussions casually, and then in a group, on Enlightenment ideals. Putting in 110% is literally impossible–unless you’re Moneke. He cared so much about us, about our learning, and about history, that it made everyone else care, too. He had constant energy and positivism, so much so it flowed out to anyone around him. There was never a dull moment with Moneke.

One of the worst teachers I’ve ever had was a middle school P.E. teacher. I remember him being unapproachable, unless you were a popular jock. He cared about your ability to succeed–if you were already athletic. Even when trying your best, you would still be overlooked, because he preferred the less-than-kind jocks that he could relate to.

I am really good at being a student. I can’t help but care, even if I don’t actually care about the subject long-term. I manage my time well, and get things done (and well) several days early, most times. I often find myself accidentally becoming teacher’s pet, although this happened quite bit more in K-12, much less so in college. I used to think it was because all my teachers knew my mom and sister, and I’m sure that was a big part, but then I started having teachers who still favored me, even when not knowing my family. It probably happened because I actually tried in high school, and teachers liked that. Although my main subjects have always been reading and writing, I’ve been “good” at math, science, and history, excelling beyond the average honors student in each subject at one point or another. I think my secret is not that I’m smart, but that I care too much, and work really hard.

JR 18

Being bilingual allows one to kept their identity within each culture. However, Anzaldúa describes the multiple sub-cultures she participates in within her two main ones, and how in each sub-culture and change of environment, her language with the people around her changes in different ways. She’ll speak one way around family, around Mexicans, Chicanos, and it will change with the various places she meets these people. Language is a living, fluid thing that constantly evolves through the years, and changes with the context of communication. Anzaldúa believes that cultural or ethnic identity is built upon linguistic identity.

- Standard English

- American Signed Language

- Signed English

- Signing Exact English

- English Slang

- Internet Slang

- Memes

- Some Spanish

Internet slang is a very internet-culture specific phenomenon. Other languages you can learn the language without being in the culture, but one cannot truly learn memes/internet slang without being on the internet consistently. I’ll use these jokes/references/speak when talking with my sister or my friends, but never my parents or any adults. It is such an ingrained part of that culture that most people will forego even explaining it to people who are not a part of it. This slang gives me the opportunity to bond with other people in an enjoyable way, and allows me to navigate and understand the internet with ease. Memes are kind of like the inside joke that you had to “be there” for, except anyone can be in on the joke across the world, which is a really interesting part of online communication, and gives one a lot of access in communicating with others.

This helps us understand that while we are helping our bilingual student writers follow directions with an American mindset and linguistics, they still have another identity that is important to them, and part of who they are. In the vein of speaking different “languages”, we can help them understand how to best “speak” the formal English writing language, through the unspoken rules, such as not using first person, to how to better structure sentences to create a stronger point or voice.